These recordings are the result of a 20 year collaboration with the Cretan lyricist Mitsos Stavrakakis which simultaneously reflect the early work of the ongoing musical project “Labyrinth”. The first recordings are from 1982 and concern themselves entirely with the idiom of Cretan music, although the influences of other related musical traditions are readily apparent. At that time I was living in Hania on the west end of Crete, and was entirely submersed in Cretan music. I was also still studying under my teacher, the late Kostas Mountakis, whose influence on my playing at the time is quite clearly noticeable. In those days Cretan music was very different from what it has come to be today. It was much simpler and clearer, and was a direct reflection of a much older aesthetic sense and order, which has today been either seriously distorted into folkloric mannerisms, or buried entirely under a façade of urban modernity. Nothing, however, remains the same forever and Cretan musicians, even at that time, seemed to be in search of new sounds and forms, whilst remaining equally insistent on maintaining a characteristic sound, which they felt to be very much theirs. I also shared their interest in this, but because my background and perspective were quite different, I approached the problem from a completely different angle. When a given musical traditions finds itself consciously searching for a new sound, it is usually an indication that the society from which it emanates finds itself in a situation of some sort of isolation which is somehow unnatural for it. In societies where there is regular contact and exchange with other related cultures new sounds and forms occur as a matter of course and the whole process usually does not inspire in people a conscious sense that something new is needed. In the example of Crete in the twentieth century though, the former would seem more likely to be the case. Crete, throughout its very long history, has always been a crossroads and a meeting point for influences from a wide variety of different civilizations, a fact that has definitely contributed to its very distinct and individual character. The historical and political events of the 19th and early twentieth centuries had the obvious result that it became a part of the Modern Greek state, and that cultural dialogue with the other peoples of the geographical area in which it finds itself was not a priority. This was, of course, the inevitable result of the turbulence of the times surrounding the emergence of nation states in the Balkan, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern regions in general. It is a well-known fact that, not only the Cretans, but indeed the majority of the peoples of these regions found themselves for many decades in a state of cultural isolation from their neighbors, and that, for better or for worse, this certainly represented a break from the previous reality of the area. Unfortunately, most of the various peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean, throughout the 20th century, had a tendency to look upon their neighbors with either disdain or even animosity, and all had their eyes turned towards Western Europe as a cultural example to be followed. Whatever the results of this attitude might have been in the political and social spheres, it certainly produced some rather uneasy results in the realm of the regional indigenous music of each of the new nation states that emerged. The massive expulsions and population exchanges of the early 20th century further complicated matters of course, as did the urgent need, felt by all, to create a homogenous national identity that would simultaneously support the ideal of the historical integrity of national continuity as well as that of European orientation. Basically all of these circumstances, and many more, eventually led to the Westernization and urbanization of local musical idioms, given that “acceptable” influences came from urban centers, which were then unanimously regarded as the beacons of contemporary civilization. Rural culture was usually regarded as being inferior and desperately in need of the “civilizing” effect of the often somewhat distorted European values promoted by the urban centers. In my early years of working on Cretan music, it quickly became apparent to me that, if one is interested in new influences which could potentially contribute to the renewal of Cretan music, the obvious place to look first would be to the related traditions of neighboring peoples, with whom a dialogue has been ongoing for centuries, and with whom innumerable common denominators already exist. The common ground shared by Cretan and European music is very little indeed, and even contemporary Greek urban music, which has, until very recently, been singularly adamant about refusing to accept influences from rural traditions, is, in many instances, nearly equally distant (In fact, perhaps the most significant common ground shared by contemporary Greek urban and Cretan music is that they both accepted influences from Asia Minor in the early 20th century). This is even more surprising when one considers that a, perhaps, disproportionate number of composers of contemporary Greek urban music are themselves of Cretan origin. A fact which, only in a very few cases, is actually reflected in their work.

My own work in the field of Cretan music is of a highly personal nature and, in no way do I lay any claims to what is generally perceived as authenticity. Equally, I do not consider myself to be a “traditional musician” per se, at least not in the usual and generally accepted meaning of the term. I have been deeply enamoured of many different musical traditions during the course of my life and, though I am acutely aware of the uniqueness and individuality of each of them, I never saw any reason to compartmentalize them and draw boundaries between them. This is especially the case when I find myself looking at traditions which already share a considerable amount of common ground. Perhaps for this reason it seemed natural to me to place a Cretan lyra alongside an Afghan rabab, or a Turkish saz, or even an Indian sarangi (a distant cousin of the lyra itself). To use a guitar however, an instrument with which I am at least equally familiar, is something which does not naturally occur to me. Cretan music is not based on chordal structures (something for which the guitar is ideally suited), and the guitar is not designed to render melodies which include microtonal intervals (an essential component of Cretan music). Apart from these practical and technical difficulties, which are not necessarily prohibitive, there is also a question of aesthetics. This, of course is always a rather personal issue, and so it should be, but I do feel that there is an inherent aesthetic kinship which links modal musical traditions, which, I believe, no one can really in all honesty deny. It also seems to me that the fusion of modality and polyphony very rarely results in anything more than a serious compromise of both. For this reason, I felt compelled to maintain the modal integrity of Cretan music, and this almost automatically pushed me in a very specific orchestrational and aesthetic direction.

The lyrics of Mitsos Stavrakakis interested me particularly because they are, on the one hand, full of very vibrant and intense images, and on the other hand, because they make use of a traditional linguistic idiom in a very contemporary yet uncompromising way. The voices of Vassilis Stavrakakis and Spyridoula Toutoudaki are ideally suited to Mitsos’ lyrics and, for me, bring them to life in a very unique way.

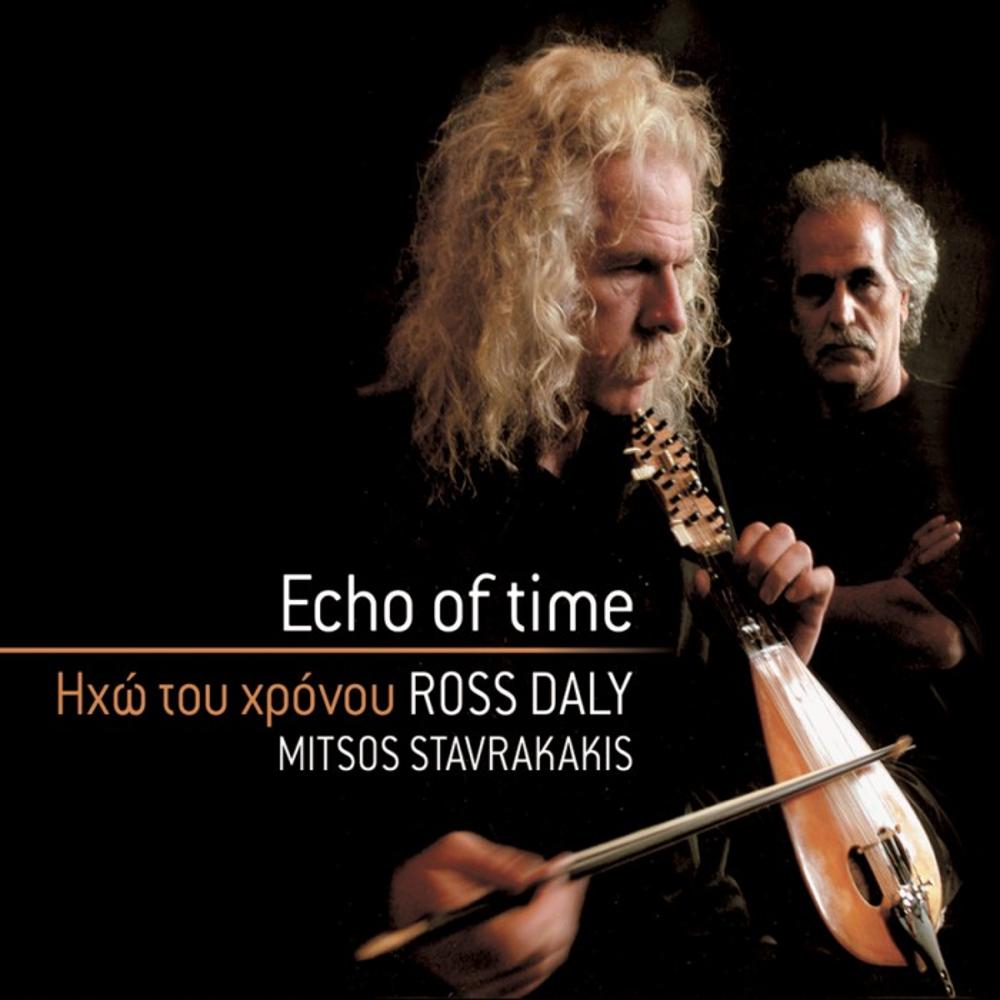

Ross Daly